At the start of this year, I wrote a short article, The Intermittent and Compulsive Viewer (which can be found Here, also on this blog), in which I discussed and examined what I identified as the two primary types of audience perspectives in relation to film, and in so doing, using myself as the experiment, I took a sample of my ten favourite films, which I declined to name at the time. Although I wrestled over my final spot in what I referred to as 'The Chase for Number Ten,' the fact that I was able to name nine, most of my favourite films, with relative ease, put the idea in my head that I'd like to do an article on it at some stage.

To be able to hone things down, refine it into a definitive form, being able to say that "this is what it is," with confidence, is something that has eluded me for a long time. Even during my years in writing extensively in the realm of film criticism, I was never able to pinpoint my opinions onto any one thing. In this way, my growth as an artist has been of a great benefit to any critical insight I may claim to possess. Although I am much more interested in pursuing my own creativity, having done works in various mediums, including my first novel, poetry collection, and finally a first draft of a feature-length screenplay, a lockdown project of sorts, has given me a view I would not have been able to attain otherwise. I now have the ability and willingness to legitimately assert and believe in myself without feeling the need to shout about it and demand attention Also, coming off the back of a major project with my first screenplay, I have decided to ease off a little, do something more along the lines of indulgence and, dare I say it, FUN!

I always have been and always will be a writer, but the movies were my first love as far as artistry, so I'm going to kick back and have a bit of a time of it with this one. While I will be discussing things in a somewhat serious and critical fashion, I aim to do my earnest to broach the subject in a manner that involves as much my own relationship to the works, elucidated by little stories and tidbits, hence the subtitle of the piece. Hopefully I don't bore you all to tears in the process.

#10 - A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

Although the first nine choices for my list were fairly easy to pick, the same could not be said for number ten. Perhaps it was because it was the final spot, and in doing so I deny the inclusion of so many great films worthy of consideration. However, after some time, I came to asking myself, "what about A Clockwork Orange?" After all, it was the first film I ever declared as my favourite, and it proudly remained so for some time. Had it fallen so in my estimation? When I thought about it, my answer to that question was "no." Of all the lists I've ever written up provisionally (including a top ten submitted to Empire Magazine as part of their 500 Greatest Films of All Time feature many moons ago), I think it is the only one which still remains, as much for sentiment as anything else. I remember seeing A Clockwork Orange as a teenager and being completely entranced. Of course, although I was young in my self-education, I had heard all the hoopla and fuss, these murmurings and snippets you'd get from time to time if you were watching, say, a Channel 4 special about the history of the movies. It was one of the last films before the advent of the age of digital cinema when, lets face it, no movie is ever truly banned, but I remember seeing adverts on the television when I was about eight or nine of the vintage trailer as the film was being released (if you haven't seen it it's an extraordinary piece of work, artistry in it's own right, and that's high praise coming from someone who normally loathes trailers and marketing. Check it out HERE) and thinking, "well, that was different." I didn't remember much about the content, but it left a subliminal impression indented on my consciousness that has never really went away. Stanley Kubrick was, and is, a filmmaker who appeals to my sensibilities. I love the meticulousness and obsessive craftsmanship of his pictures, their attention to detail, their immaculate framing, camera movement and angles, the particular aspect of their set designs, the jarring cuts and just the way in which he looks at the world. One cannot talk about the aesthetics of A Clockwork Orange without mentioning the music. Notwithstanding Beethoven, Elgar, Rossini (and then some), the original contributions of Wendy Carlos and her delirious bastardisations of previous pieces by the aforementioned Ludwig Van and Purcell (and who can forget Singin' In The Rain?) contribute immensely to the texture and sonic soundscape of a most distinctive and unique character. It is also probably at least partly responsible for my continuing love and veritable fetish for all things electronic and synthesised. Furthermore, at risk of sounding like a prematurely-aged haggard old fart, I had my own rebellious phase, and I guess I saw a sort of kindred spirit in Alex as he and his droogs as they waged their own war against society at large, which I did and still do see in many respects as a corrupt force and agency. Based on the wonderful novel by Anthony Burgess, in much the same way as he would later adapt Stephen King's The Shining, although remaining relatively faithful to the source text, this is very much a Stanley Kubrick picture. It kicked up an absolute fuss and a stink when it came out, and while I'm no stranger to danger and the odd bit of work that could be considered controversial, there is just something different about A Clockwork Orange. The dialogue of Burgess' invented Nadsat slanguage is elegant and entrancing, and Malcolm McDowell, in one of the most singular performances ever committed to screen, commands the piece with his presence. You might not agree with the questionable antics depicted in the film, but Alex is a charming, erudite, intelligent and sympathetic narrator as he whirls his way like a dervish, making merry as he kicks the crap out of this dystopian wasteland. It's hypnotic, seductive, deliciously funny and thought-provoking, particularly as it pertains and exhibits, through state and Christian perspectives, the nature of free will. I suppose that's what makes it so dangerous and why so many people had a problem with it back in 1971. Heaven forefend we show a young dilettante out having a whale of a time while engaging in such horrible and wicked acts of depravity. This is part and parcel to the power of the latter part of the picture, as Alex, though being compelled towards good, is quite clearly loathing every minute of it while the squares do their worst with him. It's remarkable to think that it is near fifty years old, as it holds nothing back in it's ability to shock and agitate in these supposedly more enlightened times.

#9 - Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999)

At first, I find it a little crazy that, considering my love for Japanese culture as a whole, that of all the many pictures I've seen from this country, Audition is the one that stands out for me as the greatest. But then I think about it, and I understand, know, exactly why it is so, and that is because it is a particularly unique and special picture. It was from Ryu Murakami's novel by Daisuke Tengan, who at that time was most famous for working on his father Shohei Imamura's Palme d'Or winning picture The Eel. Miike too had a connection to the great master, having picked up a credit as assistant director on one of his films. He would also graduate from the Yokohama Vocational School of Broadcast and Film, of which Imamura was founder and dean, although Miike would claim to rarely attend his classes. Neither were known for working on horror films, but both were enthused by Omega Project, the company behind the massive success of Hideo Nakata's Ring, and their enthusiasm to do something different. Boy howdy did they ever. Shot in only three weeks, which might sound like a breakneck pace, but this is Miike-san we're talking about, and he averaged a two-week production schedule around this time. It stars Ryo Ishibashi as Aoyama, a middle-aged producer and widower who, alongside a colleague, stage a fake audition in order to find him a prospective partner, and very soon he settles on and becomes fascinated with Eihi Shiina's young Asami. Now, while that may not jump off the page and shout "SCARY MOVIE!," believe you me when I tell you it is just that. Part of what makes Audition work so deceptively well in this regard is that on the surface it is so innocuous and placid. Through an extended introduction which occasionally veers into the territory of campy oddball humour, it takes the time to establish the story and characters with legitimate depth. Tom Mes, who has written extensively on Audition outside and in his book on Miike, Agitator, on the three-dimensionality of Aoyama and Asami. These are no cardboard cutouts, but very real and sympathetic human beings. Also, the way in which the film is constructed through Koji Endo's elegant score, the subtlety with which the cinematography and the editing works upon our subconscious. Though aesthetically gorgeous, we start to feel unnerved, become aware that something is going on, working on our perceptions, creeping up on us. Though we cannot see or hear it in the conscious sense, we can feel it unconsciously, and when it does come round, the only thing I can equate it to is someone sneaking up on you, bursting out of the dark to whack you on the head with a sledgehammer. Then you realise that the normal rules which protect you don't apply here and you have lost all control. At the beginning of the notes in his booklet for the old Tartan Asia Extreme DVD of the film, Joe Cornish write "'It's a romantic drama for the first hour then you get plunged into hell.' That's all I'd been told about Audition before I first saw it, and it's all anyone needs to know." I agree with that sentiment, but I also feel the need to add, without elucidating on plot details that might suggest spoilers one way or another, that it is a highly empathetic picture which lacks anything in the way of lurid exploitation and glorification of types of people or some of it's subject matter. This is a rich, dense picture with a lot to say about the world we live in and has, if anything, only become more and more prescient, particularly with regards to male attitudes towards women. As I bring this entry to a, if not swift conclusion, then certainly (I feel) an appropriate one, I should relate the story of the first time I saw the film. I was about seventeen or eighteen, and it was one of a couple of films that had been vetoed by my folks to receive their approval before I watched it. I waited until they were out of the house visiting friends and put it on, and by the end of the film I had been on the phone completely shaken as I apologised to them for doing so. The following day, indentations of my fingers would remain imbedded, imprinted into a cushion I had been gripping in nervous tension. To this day, although I recognise it objectively as one of my favourite pictures, I have probably only seen it half a dozen or so times, and can only watch it every year-and-a-half to two years because the whole ordeal terrifies me to such an extent and takes it out of me, losing none of it's power or potency as time passes. Beautiful and frightening, it is, for me, the greatest horror film ever made.

#8 - Festen (Thomas Vinterberg, 1998)

The first time I saw Festen was in university (I believe it was as part of my studies for my Film and Sound module). I sat in the screening room at the Queen's Film Theatre knowing nothing about the picture and ended up utterly gobsmacked. In a manner not dissimilar to that of Audition, it starts off so seemingly pedestrian. A family gathers from their various places to gather for the 60th birthday celebrations of their patriarch. So far, so normal, right? Only, from the get-go, there is something slightly off. Festen was the first film to 'abide' by the rules of the Dogme 95 laid out by Thomas Vinterberg and Lars Von Trier in their faux-sérieux manifesto's Vows of Chastity. The movement was established partly in jest and partly in resistance to the gross expenditures and technicalities involved in big-budget Hollywood filmmaking. As such, Vinterberg's approach as a director is striking, in that the raw, stripped-down aesthetics presented, such as handheld camerawork (inventively executed by Anthony Dod Mantle) and exclusively diegetic sound (as in to be produced live on-set), create a reality so confrontational that it ventures into a kinetic hyperreality, almost surreality. Also, far from being limited by these rules, Vinterberg and his cast and crew flourish within the confines, creating a fascinating dynamic which does indeed "take back power for the directors as artists." While there are moments which could be described as stylistic flourishes, largely because of the intelligence with which they are implemented into the setting, Vinterberg and screenwriter Mogens Rukov created a scenario nothing less than incredible, and the ensemble cast of those playing the many parts in the film, from top to bottom, the largest role to the smallest, are note-perfect. As I said, I went in knowing nothing, and that is the best way to see it (see almost every film, really...). However, there does come a point in the film, once we get to know the characters, settle into their shoes, find out a bit about the location, the family hotel, when we are beginning to get comfortable in our seats, that things are turned on their head, and from there, you are completely on edge and don't know which way to turn and what way or how to make hide nor hair of what is going on. It just bores itself into your core in such a manner that you start to doubt yourself as you ask the necessary questions and try to put the pieces together. Festen works in so many ways. It is, for me, the exemplar in the cinematic subgenre of the family drama. As someone who has a particular interest in this area and also very much invested in my own family, this of course tickles my fancy, but also, while the Dogme pictures claim not to be genre films (number eight of the Vows reads, "Genre movies are not acceptable."), once we reach the particular turning point (if you watch it, you'll exactly when I'm talking about) the film almost becomes a psychological thriller and is nerve-wrackingly intense. In as much as a family and all it's myriad parts can be taken as a representative microcosm, it has a lot to say about society as a whole. Also, from the standpoint of being a purely self-contained piece of drama, it is gripping and highly condensed, compressed filmmaking. Although being one of the newer, more recent entries on this list, I would say it one of the lesser, perhaps least well-known, but I urge you to seek it out. It's a real treat of a picture that offers up something new every time I see it.

#7 - Toy Story (Lee Unkrich, 2010)

It's hard for me to say anything about Toy Story 3 that hasn't been said already, either by others more qualified or by myself. I've been banging on about it extensively, ad nausea some might say, for ten years now. Time continues to crawl, though it feels like yesterday since I first saw it upon initial release, and it has lost none of it's magic. Over and over, at least once or twice a year I have watched it and I am taken back to the same emotions and feelings of a decade ago. I wrote an article recently on the twenty best films of the 2010s in which I declared it the best film of the decade, a declaration I stand firm beside. As I went into a lot of detail in that particular coverage of the picture, I will instead elucidate on my personal history with the film. I saw the film in my favourite cinema, The Strand, with my good friend Daniel Kelly, and it is one of the wonderful experiences I have ever had watching a film. You can tell something really made you laugh when your face hurts and your stomach is in stitches, and I was consistently howling throughout. It warmed and touched my heart with the sheer blissful quality and joy with which it is infused. It really is just the most sincere and charming picture. I was even scared at different parts, fearing for the plight of the characters. For much of the last section of the film I was turned to one side in floods of tears (I found out later my friend was turned to the other side doing the same thing!). Really, I ran the full gamut of emotions watching Toy Story 3. Without fail, it done everything I could ever ask for from a film, which is why I gave it Perfect-10 rating when I reviewed it for my blog, and over ten years of film criticism it was the only picture to achieve such an accolade. It just hits everything right. Even the kitschy, cheesier stuff as far as humour I can swallow because it is such a lovely picture and it does it all for the right reasons. Over the years since, I have watched it with family and friends, people young and old, and myself alone. Okay, I'll admit that some things are not to everyone's tastes, and there might be the odd folk out there who goes "Why is that in your list and not X? That's one of the greatest films ever." One, it's my list, and two, I have never yet been in the company of people who are not moved in some description by this film. I can't imagine a more universally acceptable go-to film to put on under any circumstances, whatever your mood is or who the audience consists of. Admittedly, of course there is a sentimental value involved, given how important the original films were to me as a child (and I am at heart a Peter Pan esque man-child who has never really grown up), how Pixar for me are the true studio of dreams, the wonder-makers of our time. That being said, looking at from as an objective standpoint as possible, I can still say I am safely assured that, without a shadow of a doubt, Toy Story 3 is one of the greatest films of all time.

#6 - Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

In a strange polarity to my previous entry, which could be called "all things to all people," Ingmar Bergman's mysterious and enigmatic Persona could be described as "everything and nothing." I truly believe that as a picture it is as close as you can get to a blank canvas. That's not to say that there isn't anything there. Far from it, I find the picture to be infinitely dense. It is is an open door into the unconscious, but how you interpret what you're seeing is down to you, in as much as it is about what you bring to the table as what has been presented. It is like a Russian doll or peeling an onion, in that with each layer being removed, another is revealed, until you reach the very depth of being, and when you get to the end, you are left with the individual self, the questions of what you are to make of it. Thomas Elsaesser equated the critical analysis of Persona with the ascent of Everest for mountaineers, "the ultimate intellectual challenge," and Peter Cowie wrote, "Everything one says about Persona will be contradicted; the opposite will also be true." It is quite astonishing how one is able to compact and compress so much information into an eighty-minute picture. Not to be dismissive of any of the great studies done on the film by the likes of Susan Sontag, as it is a marvel to discuss, mull over and pick apart, I prefer to follow Bergman's path. Given that I am devout when it comes to the cerebral response and experience, the great maestro's wish that his film be felt rather than understood rings true. As for Bergman, I don't think I've made any secret of the fact that I believe him to be the greatest of all filmmakers. What drew me to him was the fact that here was a serious artist who addressed the biggest subjects, the widest themes, in an engaging and accessible manner which is no way navel-gazing or pretentious, but also refusing to pander or compromise his vision by demeaning the audience's intelligence. To amass not only an abundance of work but that of a consistently high standard is something one should aspire towards but only very few ever succeed in achieving. My relationship with Bergman began as a teenager when I saw The Seventh Seal as a teenager in the Queen's Film Theatre and was profoundly moved. Though I would go on to see many of his films, it remained firmly entrenched in it's place. However, over time Persona grew on me, worked assiduously until I grew to appreciate it for what it is. The composition of the picture is immaculate, with Sven Nykvist making wonderful portraiture of the faces of Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson, and the splicing of the various elements by Ulla Ryghe is spectacularly put together. Bergman would amass an oeuvre unlike any filmmaker before or since, but with Persona he would reach his ne plus ultra. Not only is it very much a classical Ingmar Bergman film, it goes above and beyond any standard formula or aesthetic he may have worked out up until that stage. Anchored and bolstered up by the extraordinary lead performances of Ullmann and Andersson as Elisabet and Alma, it is a work of unfettered, unrestricted experimental radicalism that goes beyond the avant-garde and postmodernism, or even psychoanalysis and dream logic, breaking all the rules and conventions to invent it's own, if indeed there actually are any to be followed. It dares to, and succeeds, in the execution of things which really should not be possible. Bergman is an artist who bores a hole down into the core of being; many of the things I would describe as among the most terrifying in cinema are in Bergman films, and he only ever made one horror movie (at risk of using a boring old term, the highly underrated Hour of the Wolf). He also has provided some of my most humorous and joyful moments, and yet is not a comedian. And then there are the times of transcendence that go beyond words... Bergman was capable of all those things, and nowhere is everything exemplified more so than in Persona.

#5 - Au Hasard Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966)

And now for my next entry, also from 1966, is a film which Bergman would famously describe as "completely boring." Believe it or not, on this one I actually tend to be in the camp of an artist I sometimes take issue with, Jean-Luc Godard, who said, "Everyone who sees this film will be absolutely astonished... because this film really is the world in an hour and a half." The late Donald Ritchie compared Bresson to the cinematic equivalent of a litmus test when taking note of the varying reactions of he and his friends to the director's pictures. Now, while I can hardly say the same, for when I pitch Au Hasard Balthazar to my friends as this wonderfully beautiful film with a donkey as the main character, I can imagine some of them are probably like, "Okay, there's Callum with one of his 'out-there' suggestions again..." However, I cannot recommend this picture any more than I am about to. Along with the previously mentioned Audition, it is one of two films in this top ten list that I can only watch intermittently, because by the end I am reduced to a complete wreck. No film I have ever seen can conjure such up floods of tears. I won't get into plot details as to why (though of course that is a large part of it), but instead I will elucidate, or at least attempt to give a semblance of an impression of the feeling Au Hasard Balthazar triggers within me. It's as much about the way the story unfolds as the story itself. Exquisite in it's simplicity, this is not traditional storytelling in the classical sense associated with cinema, but more along the lines of a parable, an allegory, a fairy tale, in stripping something a narrative down to it's bare essentials. This is myth as truth, presented through the omniscient, omnipresent saint/Christ-like figure of the donkey Balthazar as he observes and participates in the lives of his various owners, most specifically Marie, played with understated brilliance by Anne Wiazemsky. Perhaps part of the reason I have stepped back a little from regular criticism is because I have in later years preferred to avoid over-thinking, turning everything into an intellectual exercise. The longer I live, the more I lean towards a sort of purity when it comes to feeling, experience and emotion. Not that Balthazar is lacking in content, far from it. It quite clearly has a lot to say about spirituality and faith, struggle, strife and suffering, and as they pertain to life itself. It's just that something like this speaks to my soul, the very heart of me, and I think that is something beyond words or a clinical exercise in critique. It demands a different sort of approach, and I find myself favouring this kind of asceticism, in life and in art. I think what Bresson does here is it's prime example in cinema. Balthazar is so minimalist in every aspect of it's composition, from the naturalistic performances by a largely non-professional cast, to the technical aspects such as the cinematography and editing, and the sparse use of dialogue and music, that the effect of it's impact is almost startling. We are so saturated with showy acting, glory shots, moments of bravado in mainstream movies, obsessed with their own brilliance, vanity and grandiosity, that to see something like this is positively refreshing. But this is not to say it stands as a contrast, a mere juxtaposition to everything else. Au Hasard Balthazar is a distilled essence of life itself, condensed and compressed, like a message in a bottle, into a ninety-minute picture.

#4 - Withnail and I (Bruce Robinson, 1987)

Here we venture off into different territory. Don't excuse the bold statement I am about to make, because I certainly won't: Withnail and I is the greatest comedy ever made. Now, while that may be so, and, yes, I have more than something of a soft spot for this particular entry, it is above the status of base indulgence, for with great reflection I do believe that Withnail and I stands comfortably head-and-shoulders alongside any of the greatest films ever made. I don't need to say that in order to make it true: I just know it to be so. I think I saw the film, as with many over the years, at a way too young age, probably about eleven or twelve or something silly like that, and although I didn't think as highly as I do of it now, I always thought it was a rather unusual little film. It was only as a teenager and as an adult I grew to appreciate it's brilliance. Bruce Robinson, writing and directing a story based upon his own personal experiences, takes us, in the guise of the title characters, through the ribaldrous escapades and adventures of two unemployed actors in September of 1969. Wonderfully played by Richard E. Grant and Paul McGann, the two serve as a superlative example of a yin-ying, buddy dynamic, each representing different aspects, wholly unique parts and perspectives on what is going on, the trials and tribulations, often self-inflicted, of their situation, and the chemistry they share, bouncing off one another in their tete-a-tetes, is simply unmatched. The very strange world of these two down-and-outers in London, seeking to get away from the insanity of the big city and the various vagabonds who populate it, escaping to the country for recuperative refuge and revitalisation, only to be surrounded by a cast of equally outrageous individuals, is nothing short of absolute hilarity. It is for pictures like Withnail and I that the term 'cult film' was invented. Everything, right down to the score by David Dundas and Rick Wentworth just screams eccentricity. However, by no means does this venture into the territory of quirk, that dangerous trend of being offbeat for offbeat sake, attempting to patch over an absence with the bizarre, as I feel a number of certain people have attempted to do with their works in the years since. The reason that Withnail and I works is because although it is a movie of an odd disposition on the surface, there is a substance beneath it all, an element of truth speaks behind everything. Maybe it is because I have been in many similar such silly situations, got up to the same kind of antics, particularly where alcohol and money is concerned, the struggles of the artist, or just, quite simply, what it means to live. Not only is it in many ways a work of kitchen-sink social realism, there is a plain and simple honesty to it, exhibited in particular by writer-director Robinson and his two leads Grant and McGann, that just hits home hard and never fails to touch my heart every single time I watch it. That is when I'm not laughing, or, indeed, sometimes when I'm in the middle of laughing, and I laugh a lot, probably more so than I do at any other film. It is endlessly quotable, so many moments and incidents occurring which sound like the kind of story you would tell down at the pub with your mates, people like Ralph Brown's mysteriously insightful and philosophical drug dealer Danny and Richard Griffiths terrifying lecherous Uncle Monty (for my money, one of the funniest characters in film history), right down to the smallest of parts, that stick out in your memory. Earlier on I talked about accessibility, and this is one of those films. I have seen it in just about every conceivable situation; drunk, stone-cold sober, horizontal and hungover, alert and wide awake, on holiday and at home, lying in bed on my iPod or a big screen, with friends and family. Even my mother, bless her, the single most notoriously hard person to gauge a picture for, the harshest and fiercest critic of the movies I have ever seen, loves Withnail and I. This is autobiographical art and low-budget filmmaking at it's finest.

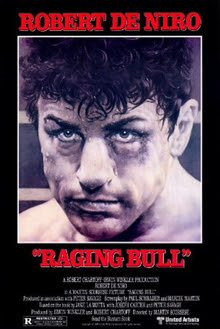

#3 - Raging Bull (Martin Scorsese, 1980)

I have alluded in the past for my love of Raging Bull. Last year, I wrote a piece on Martin Scorsese with his latest fictional feature, The Irishman, as it's basis, and in that article I declared Scorsese as "America's greatest filmmaker," something I firmly believe in. As a filmmaker in the United States, he is without parallel in terms of the consistent standard of excellence in artistry. However, much as I can appreciate the picture for it's supreme technical achievements (the immaculate cutting of Thelma Schoonmaker's editing, the beautiful framing of Michael Chapman's black-and-white photography, the extraordinary sound editing by Frank Warner) and as a sum greater than the product of all it's parts, my journey with Raging Bull is a very personal one. I first saw the movie when I was way too young to fully appreciate it for what it was. I just don't think I got it. Later, I became enamoured with Scorsese, in particular Taxi Driver, which was my favourite of the director's work for a long time and still holds a place of great meaning and significance in my heart. However, in university I rediscovered Raging Bull in a number of different ways. It was being played as one of the core pieces for a module (I believe it was Film and Sound, but it could have easily been Music in Film or Hollywood), and indeed it would also crop it's head up and become my selected question during my seated/timed examination, but I had also been in the process of creating a wholly different relationship with the film. You see, without going into things in any great detail because that's a story for another day, a number of incidents had occurred in my life that were fairly 'shaping,' shall we say, and at the time I also was dealing with different issues for which I felt the need to attend counselling. One of the people to whom I am grateful for helping me once I asked me in one of our sessions, "If you could name a movie that you see as representative of your life, what would it be?" I couldn't furnish or provide an answer on the spot, not only because my contentiousness instinctively railed against what I probably felt was a poxy line of questioning, but because I didn't have an answer to provide, the ability to translate cohesively and equate something to the emotions I was dealing with. However, I had recently been developing a bit of a fixation with Raging Bull. I had seen it at least twice before and it didn't click, but all of a sudden around this time I picked it up again, and it was like a flip switched, a lightbulb went off into my head. Maybe it was the supreme commitment of Robert De Niro's performance as Jake La Motta, perhaps the greatest in all the history of screen acting, and those of his supporting cast, specifically Joe Pesci and Cathy Moriarty. Maybe it was the honesty and realism of the screenplay by Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin. Maybe it was the mastery of the craft by director Scorsese, or even, quite simply, the stirring music of Mascagni. Regardless, a chord was struck. I only ever watch a movie several times in quick succession in one of two scenarios: one, if I develop a fixation, and secondly, if I think the work is a masterpiece. Raging Bull ticked both of those boxes, so when I returned for another session some time later, I realised I had an answer to the counsellor's question. The story presented onscreen of Jake La Motta, this animalistic brute of a man on a self-destructive path of obsessive rage who threatens to tear apart his life and those of everyone around him, given my issues with angst, anxiety and anger management, was something I could relate to. It's not necessarily pleasant, but it's the truth, and through truth we come to sympathise, empathise with this churl, who, although we cannot condone his behaviour, actions or the mentality behind it, we can at least come to understand it. Maybe it's the former Catholic and reforming spiritualist in me, but I can relate to how Scorsese goes about this business. There is a sense of timelessness, modern myth-making in the most singular, even dare I say, biblical sense, through the absolute commitment of De Niro's lead performance, that elevates this as a work of art. I cannot say enough good things about Raging Bull. I admire it more and more every time I see it, but on this occasion I have decided to furnish how I praise this picture with a bit of my own story. I hope you can excuse my mild indulgence. Who knows, in ten years time it might well be my favourite film...

#2 - Aguirre, the Wrath of God (Werner Herzog, 1972)

As I mentioned earlier, I do have something of a fondness and leaning towards the art from certain countries, and I think it should be said that I am an outright Germanophile. In particular, the period in which this film was made, though under the fog of the Cold War, the-then divided Berlin between East and West, would see a cultural renaissance in Germany, particularly in the fields of cinema and music. At the forefront of this New German Cinema, as it has been referred to, were filmmakers such as Wim Wenders, Volker Schlöndorff, Margarethe von Trotta and the great enfant terrible, Rainer Werner Fassbinder. However talented those artists may be, while those filmmakers were establishing themselves back home in the streets, concerned themselves in their works with the sights and sounds of the city, their contemporary Werner Herzog was running around the Peruvian rainforest along the Amazon River with a crew and a band of natives shooting on a shoestring. I mean, people talk about troubled productions in the history of filmmaking; this is on a whole other level of legendary, for the circumstances of it's coming to be are incredible. I'm not going to furnish with some of these stories, but you should look them up and check them out. It really is a wonder that so many of Herzog's productions were ever able to be made, much less turn out to be the masterpieces that they are, and Aguirre is the prime example of this singular aesthetic. My first encounter with Herzog was as a teenager when, delirious with a fever for a week in one of my rare sicknesses (which, in hindsight, is probably not a bad way to experience Herzog's films), I managed to get through eleven of his films across two Anchor Bay DVD box-sets. Although there were many great films among them, Aguirre is undoubtedly the one that has always stood out for me the most. Right from the get-go, with that extraordinary opening sequence of the party of Spanish conquistadors and their slaves descending from the Andes, down from from the heavens and into hell in search of the mythical El Dorado, the scene is silent but for the score by Florian Fricke's band Popul Vuh, a synthesised chorus of disembodied voices played on a choir organ, the otherworldly tone and the nature of the piece is firmly established. While ostensibly pertaining to be a historical period piece and existing in a semblance of reality, Aguirre belongs to a whole other realm altogether as we fall into a strange and surreal dreamlike haze of a collective madness. There are so many moments within the film that defy traditional logic and acceptability, and yet within these particular confines are wholly acceptable, make perfect sense. Only the titular Aguirre, played with singular menace and sublime tyranny by Klaus Kinski, stands tall as our guide, indeed thrives in this guise, in a performance every bit as hypnotic as it is terrifying. A precursor to the kinds of themes later explored by Francis Ford Coppola in his 1979 war film Apocalypse Now, Aguirre, the Wrath of God continues to stand and shoulders above anything that followed in it's footsteps. Haunting and hallucinatory, while the film has much to say about the perils of colonialism, the pursuit of wealth, glory and megalomania, it has the wonderful dexterity of being both a work of epic art and guerilla filmmaking, but if anything the thing it most resembles is a fever dream. It is a throbbing, pulsating, gelatinous membrane that could be anything and everything, yet is very much it's own thing, the work of a supreme artist, and it begs to be seen.

#1 - The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984)

There, I said it, although I think I've said it in many different ways and numerous forms over the years. However, this might well be the first time I have hit the nail on the head in the definitive sense, so I feel that such an occasion deserves a bit more gravitas in bringing things round to this particular declaration, as I have been making a few during the course of writing this article: The Terminator is greatest film of all time. I could elaborate to some degree on all of the various qualities of the picture, which I think I will to a small extent, but in order to fully establish what this film means to me, it is best that I speak something of the storied, personal history I have with it instead. When I was a teenager, I was always beating on about A Clockwork Orange, and I do believe that I thought it was my favourite film in that particular present. As time went on though, I kept coming back to where, in many ways, it all started for me with The Terminator. I was first introduced to this world, like many people, through the sequel, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, which I saw on television when it was first broadcast back in the mid-nineties with my parents covering my eyes at the appropriate moments (interestingly, the version that ended up on BBC One on September 3, 1994, which I think was the one I saw, was a wholly unique cut based upon the 1993 Special Edition released on Laserdisc and VHS, not the theatrical cut, featuring the Kyle Reese scene but with edits made for violence and swearing, presumably by the Beeb themselves). Being a child who had until that stage only been exposed to Disney and similar kids fare, I was completely hooked by this thing that was wholly new to me, but my folks were always pretty attentive in trying to protect and not overexpose me to such stuff. That didn't stop me of course from taking advantage of seeing everything unsupervised at a later stage on the VCR, as much of the film had been recorded on the tape. I would later learn how to master all facets of this mysterious device. Similar recordings of broadcasts would be made over the years, left overnight to go until the tape ran out (my personal history with VHS, to this day still my favourite format of home video, is another article worth writing some day, especially as I now have one up and running again!), and so I had the privilege of seeing a lot of movies I shouldn't have. At the time I was especially enamoured with action movies featuring musclebound heroes, but was way too young to purchase them legally or receive permission to watch from my parents. However, I was far too industrious to be denied, so I just had to play the waiting game with the TV guide magazines which I devoured every week, and this was more than likely how I first came across The Terminator a number of years later. My conversion of preference was not instantaneous, but although I still leaned more towards the action-oriented blockbuster sequel, I remember being struck by the unique tonal quality of the original. There was just something strange about it, and really when I think about it in that sense today it still seems strange. The Terminator is this weird, hybrid beast of a picture: on the one hand, it is a dirty, gritty, hard-hitting urban B-movie in which the city at night is very much a character in it's own right, and on another, appropriate given the concept's origin in writer-director James Cameron's own dreams, it like something out of a nightmare. From a genre standpoint, it is pure science-fiction, yet it is a road/chase film full of action and the tenets of slasher/horror movies, and stylistically, while quite clearly a low-budget picture and maybe the ultimate in guerilla aesthetics, it also harkens towards Cameron's future in massively scaled big-budget productions. For all of it's relative compactness and compressed qualities, The Terminator is a movie of big ideas and themes, with a well-developed story, an internal universe and world, that reaches over and above, breaking out of genre-trash confines. There are so many different elements and components, lines and strands I see in this picture, that to lay it all out would be akin to a grid, surrounding a convergence point, the Tech Noir scene. The paths of the three principal characters, Linda Hamilton's Sarah Connor, Michael Biehn's Kyle Reese and Arnold Schwarzenegger's Terminator, all come together. It's an exquisite and genius piece of virtuoso and ingenuity. In a foreshadowing of Reese's later description to Sarah of the post-war future apocalypse from which he has come being the consequence of "one possible future," in the nightclub, Sarah knocks a bottle of water to the floor, and in bending down to pick it up, unwittingly avoids the attention of the tracking Terminator. I just love the idea that the whole of human history from this point is dictated by chance and happenstance. At this stage in the slow-motion shot, the interjection of Brad Fiedel's score, the metallic heartbeat of the machine, begins to play over the top of Tahnee Cain's Burning In The Third Degree, eventually getting swallowed up as all the key players slowly but surely become aware of each other's presences. Bound by fate, the tension builds and builds and builds in a silent scream until the gunshots cry out. It's a largely wordless scene which does everything that a movie should and the prime example of doing what only the medium of cinema is able to. I realise I have gotten this far without actually saying anything much about the component parts of the film that make it up, and indeed, for a personal history, I've jumped ahead about two decades in time. Then again, I've been making those sorts of leaps a lot of late, having become rather interested in certain ideas surrounding the non-linearity of time, malleability of memory, paradoxes, ripple effects in the fabric, dreams and alternative/parallel universes. I digress, but I suppose it makes sense, given their importance in The Terminator. The long story short between then and now is that the film grew on me, super-ceding the status of it's successor in my eyes, and later that of A Clockwork Orange when I realised it truly was my favourite film of all time. I developed one of my obsessions, picking it apart piece by piece, putting it back together again, and it everything always fits rather well. To this day, although it is less so of late, as with everything, given my dedication to my own studies, I still see the film at least three or four times a year, and I can safely say I have probably seen it well over a hundred times. James Cameron, although going onto make many more great films, even masterpieces, never again returned to this sort of aesthetic, and so it is a wholly singular and unique slice of cinematic history. As far as writing about it, if you'll excuse the expression, I've probably only hit the tip of the iceberg. It is pure kinetic storytelling with a continuous momentum that just never stops. For me, it hits all of my key points in every single way and is the complete synthesis of everything great art should be.

In Conclusion

When I wrote of The Terminator, I mentioned the "malleability of memory," and I think that is worthy of note because, not only does that have something to do with the thoughts you formulate, it also plays into how you relate to art, and life, as an observer, and the relationship between objectivity and subjectivity. No matter how much you try to be objective about something, and, at risk of sound egotistical or delusional, I think I've got a pretty hang of it now, the way in which we view things is inherently subjective. We are reactive creatures who cannot help but be moved, touched by the things we experience. I've learned that the influence of time cannot be ignored. If I had have done this list ten years ago, it would have looked very different (at least half the entries would not have made the list, for one thing), and the same could perhaps be said if I am to do it again in ten years time. I know for a fact that my opinions and perspectives have changed. The way I look at things as a human being is different to how I did then, and there's no reason why the same might not happen again in the future. As such, in this case, these things, lists and such, although I may be able to say objectively are representative of my views, here and now, subjectively it stands to reason that they are only indicative of the person I am now at this given stage in my life. Although, for all intents and purposes, it is just a stupid list and a bit of indulgence, these sorts of things fascinate me. It's probably the reason I dedicate myself mostly to my own work, largely abandoning critical analysis in favour of my own explorations as an artist, than I do that of other people now. Still, I've had a lot of fun with this, and I hope that you have had a little too.

Best

Callum J. McCready

June 2020